Setting the record straight on the Oakland Coliseum deal

Deal or no deal, Oakland will be left fiscally vulnerable

The deal is “on track”

That’s what Mayor Thao’s been saying for 4+ months since announcing her plan to sell the Oakland Coliseum site (112 acres including the former A’s and Raiders’ stadium, former Warriors’ arena, and parking lots). The sale would enable her to avoid massive cuts to police and fire personnel, among other critical city services.

This story has taken so many twists and turns that it’s difficult to get the facts straight. But with so much on the line — a mayoral recall and majority of city council seats up for grabs — the facts matter more than ever.

Below is a timeline of events, as they’ve been reported on and announced by Thao, city council members, AASEG, and other relevant parties. Importantly, it’s impossible to separate the Coliseum deal from Oakland’s historic budget problems, which is why you’ll see multiple mentions of budget proposals and discussions. After reviewing, these are the questions you’ll need to answer for yourself:

Is this the work of competent, fiscally literate leaders?

Is the Coliseum sale for the benefit of Oakland residents, or the people in power?

How much, if at all, is the Coliseum sale a way for Thao (and others) to preserve or gain political capital with less than a month until her recall election?

Timeline of Coliseum deal

March 26, 2024: It all started when the City Administrator, who’s responsible for enforcing the city’s budget, forecasted that Oakland will face a $177M budget deficit this year (fiscal year ending June 2024), and another $175M deficit the next year (ending June 2025). This meant that Mayor Thao had until June 28 (last day of this fiscal year) to get a revised budget approved by city council that would close the gap on the $177M deficit.

Initially, Thao planned to immediately freeze all hiring and aimed to cut all department budgets by more than 20%, including police ($83M in cuts) and the fire ($47M).

Reminder: Oakland already faced a historic $360M deficit in the prior year (ending June 2023).

May 24: Fast forward three months, Mayor Thao proposed a revised city budget, but said those aforementioned mass cuts to police, fire, and other city services would no longer be necessary, because she had reached an agreement to sell the Coliseum site to African American Sports and Entertainment Group (AASEG).

Substantively, it was a handshake deal, but the preliminary terms were that AASEG would pay $105M for the city’s 50% stake in the Coliseum site (the A’s own the other 50%).

As for the deficit, this was the Hail Mary that Thao needed to avoid cutting dozens of police officers, shutting a police academy, and suspending 5 fire engine companies, among other critical services.

However, we must ask: Is it a smart move to sell a revenue-generating capital asset to pay for operating expenses that the city can’t afford? This would be like selling your house to pay for your credit card bill!

June 12: A few weeks later, 100+ public speakers joined a city council meeting to discuss Thao’s grand plan, which posed more questions than answers, namely: How does a $105M land sale close the gap on a $352M two-year deficit?

Obviously, the answer is that it doesn't, and substantial cuts were still required. In fact, at the meeting, the Budget Administrator admitted the city still faced an ongoing structural budget deficit of $100M+ in each of the coming fiscal years. Put another way, the city is hardwired to spend $100M more on baseline expenses than it earns in revenue.

Some members of city council, specifically Councilmembers Ramachandran, Gallo, and Reid, expressed concerns over these short-minded budget tactics. Thao promised to come back with a final budget proposal, including an alternative plan that doesn’t assume the Coliseum sale.

City council also authorized the city to negotiate and sign a formal agreement to sell the Coliseum, which was largely a procedural matter.

June 25: The City Administrator submitted two different budget proposals for city council’s review and approval.

The first version — which was basically the version pitched on May 24 — banked on getting $63M in one-time funds from the sale of the Coliseum. Thao was prepared to spend money she didn’t have, and keep in mind, a final agreement had still not been signed.

The caveat: At least $15M of those funds would need to be paid to the city by September, otherwise Thao would be forced to enact a ‘contingency’ budget which would consequently cut $63M across police, fire, etc.

Police Chief Floyd Mitchell told city council that, if enacted, the ‘contingency’ scenario would have a “major impact on [OPD’s] ability to cover patrol shifts and provide basic response services to the citizens of Oakland.”

The second version assumed no revenue from a Coliseum sale. This involved similar cuts across the board, including to public safety, but the Budget Administrator said it would enable a “smoother and slightly more flexible” transition than the ‘contingency’ plan.

Importantly, the fiscal year was set to end on June 28. This meant city council members had less than 4 days to review both budget proposals, ask for and review public comments, and ultimately approve a $2.2B budget plan with potentially debilitating consequences.

Pause here and ask: Why would Mayor Thao leave so little time for city council to adequately review her budget proposal, if not to just force council’s hand to approve a budget deal before the fiscal year-end deadline?

June 28: It was the last business day of the fiscal year and the budget was due. City council met to discuss the budget proposals. It was an 8-hour marathon hearing but no budget was approved.

Councilmember Ramachandran insisted that allowing the city to spend $63M it didn’t actually have would be irresponsible, especially given a final deal with AASEG hadn’t even been signed.

Councilmember Reid criticized Mayor Thao for running out the clock: “This budget was ready for our review on May 17, and the mayor, the CEO of our city, elected not to provide the accurate and more truthful budget to be presented for us to have enough time to sufficiently review, make amendments and weigh in.”

July 2: The following week, city council met again, and this time approved Thao’s budget proposal that relied on $63M in proceeds from the yet-to-be-signed Coliseum sale. This version of the budget also included the doomsday ‘contingency’ scenario in the event sufficient payments weren’t received in time.

The budget passed with a 5-3 vote. Ramachandran, Gallo, and Reid were the three council members who voted against Thao’s budget.

July 25: Councilmember Ramachandran published a scathing op-ed calling out Mayor Thao and her city council colleagues for “[thinking] they can pay recurring bills with a one-time sports deal — but [Oakland] can’t afford the overdraft fees.”

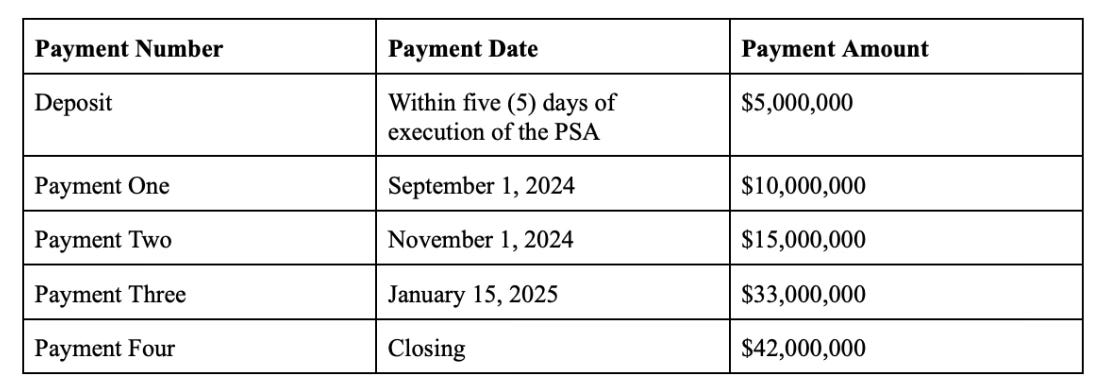

July 29: Mayor Thao announced that the city signed a term sheet with AASEG. This was the first time the public saw more detailed terms of the $105M deal, which would be paid in installments spread over 2 years.

AASEG promised to pay the first $15M by September 1, which would help Thao avoid the ‘contingency’ scenario. Cumulatively, the city was set to receive the $63M it was counting on during fiscal year 2025, with the final and largest payment due at close.

Importantly, this was a non-binding term sheet, meaning the final terms of the deal were still subject to change and no official purchase agreement had been signed.

Also notable: The sale of the Coliseum was basically a no-bid contract, meaning AASEG was the exclusive bidder since November 2021. Without multiple bidders to compete for a higher price, AASEG had a major upper hand in terms of negotiating leverage, especially considering the city’s urgent budget shortfall.

August 5: Just a week later, AASEG agreed to pay $125M to buy the other 50% stake from the A’s, which would give AASEG full control over the Coliseum site. For some reason, AASEG was willing to pay $20M more to John Fisher and the A’s than it had agreed to pay for Oakland’s half.

August 29: AASEG and the A’s signed a final agreement to move forward on the sale. AASEG paid the A’s a $2M deposit.

August 31: Thao announced AASEG and the city signed a final purchase and sale agreement for $105M, which had a slightly updated timeline compared to the term sheet announced the month prior.

September 12: In an interview, Mayor Thao said “we have [the initial $15M payment].” But we later find out that is not true at all.

October 1: At a city council meeting, Ramachandran, Reid, and Gallo voiced concerns over whether the city has received the $15M from AASEG. The city needed that money in the bank, otherwise it would have been forced to enact the contingency budget.

At the meeting, the City Administrator did not confirm that the city had received the funds, but he did confirm the ‘contingency’ budget had been triggered.

Thao’s office issued a statement contradicting her own administrator: “The AASEG deal is on track. No contingencies have been triggered that weren’t already in place.”

In recent weeks, Ramachandran, Reid, and Gallo said they all made multiple calls and sent multiple emails to Thao’s office asking for clarity on the deal — all of which went unanswered.

AASEG co-founder Ray Bobbitt said they wired $5M on September 3 and planned to pay another $10M on October 7. He said the conflict between Thao’s office and city council were “political issues.”

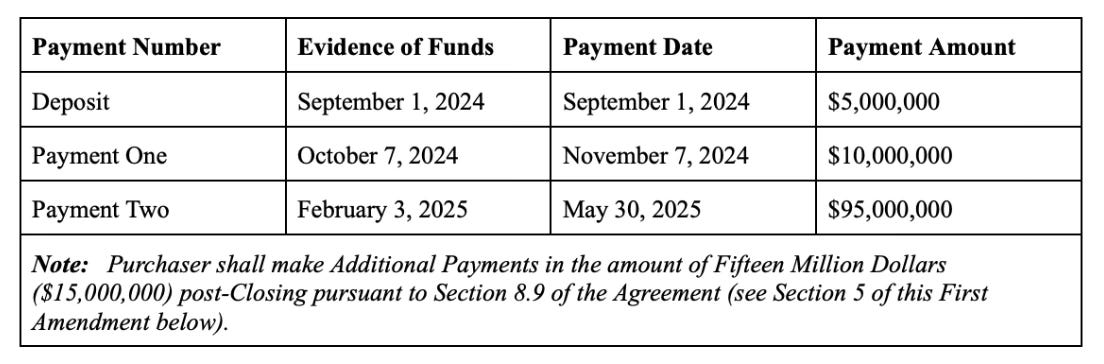

October 3: A media report said Thao’s office and AASEG had tentatively agreed to a revised deal, increasing the purchase price from $105M to $110M. The new terms were:

$5M deposit reportedly paid on September 3, 2024, according to Bobbitt

$10M due on October 7, 2024 (to avoid enacting ‘contingency’ budget)

$95M due at close, no later than May 30, 2025

By closing the deal earlier, Thao would get the money she needs within the fiscal year to cover the city’s rising salaries and operating expenses. But the revised deal price was still $15M short of the $125M that AASEG is paying the A’s.

AASEG claimed the A’s got a higher price to compensate the team for due diligence it conducted when it bought its stake from Alameda County in 2019.

Also, AASEG’s desire to close sooner reportedly came at the pressure of AASEG’s own investors, who didn’t want their money at risk given the city’s uncertain financial circumstances.

City council members weren’t made aware of this new deal, even though it would require the council’s approval.

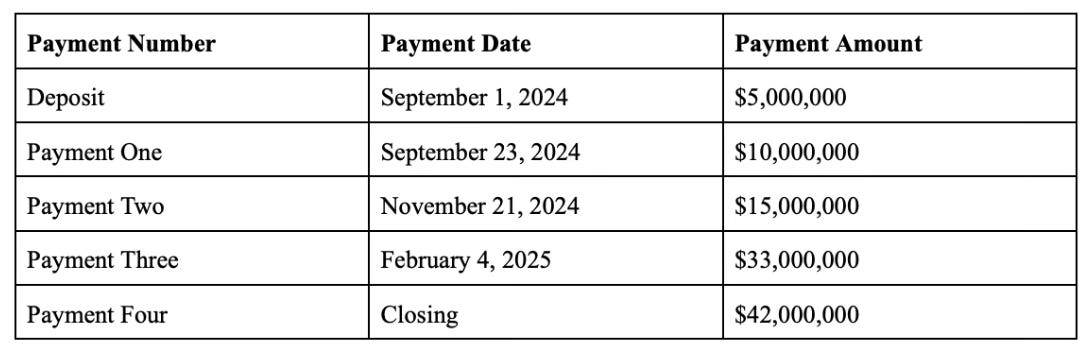

October 7: Mayor Thao announced an amended agreement with AASEG, with a total value of $125M that matches the price for the A’s. The latest terms, which are dated September 23, are less straightforward.

Upon close, the city would still only receive $110M, with the additional $15M tacked on, spread over three $5M payments, contingent on AASEG receiving certain permitting milestones after close.

3 big things

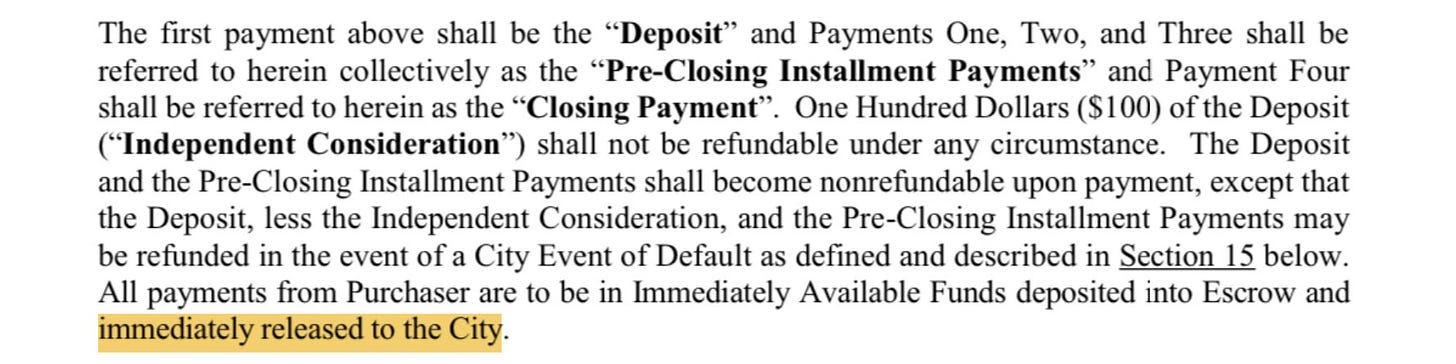

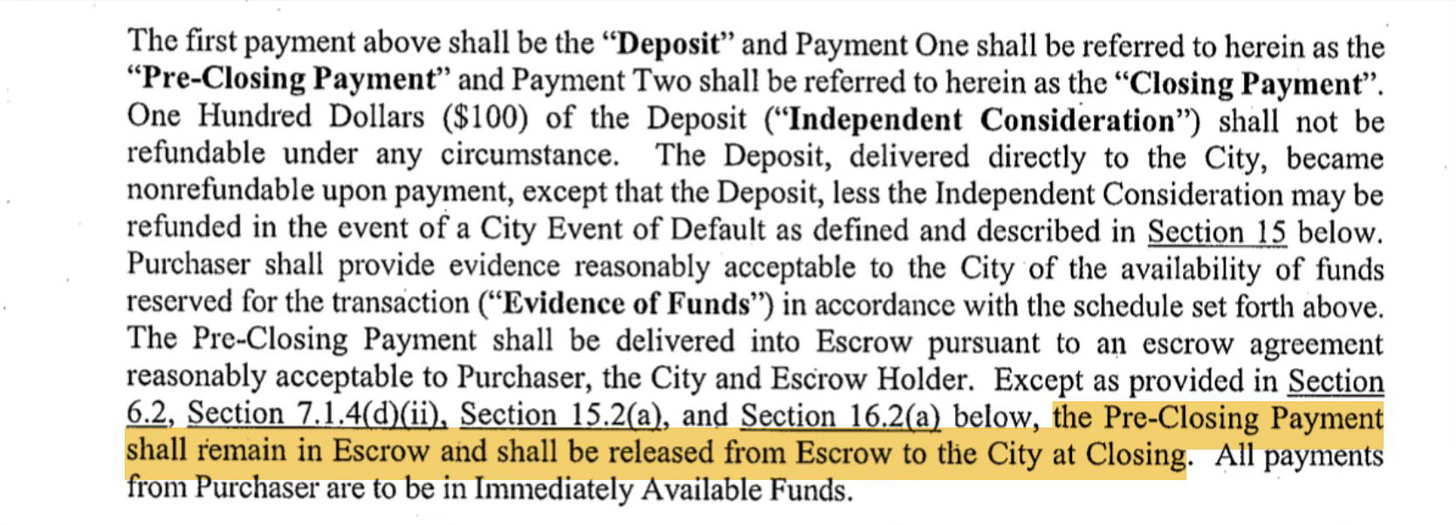

First, the city won’t get any of its “payments” until May 2025. The terms of the amended agreement clearly state that the $10M from “Payment One” won’t be released from escrow until closing, at which time the remaining $95M (“Payment Two”) would also be due.

This is an unheard of level of protection for a developer — where their installment payments are not at risk and fully recoverable before close — and it’s a stark departure from the original agreement where the escrow funds would be available immediately. Here’s a comparison showing the difference:

It also means that any statements Thao and her staff have made that the city has received money (other than the $5M deposit) are contractually false. Thao claimed weeks ago they “have [the initial $15M]” and this week her staff told media the city “received” the hotly contested $10M payment.

Key questions: Does AASEG believe the city is so fraught with risk that it’s demanding all money be kept in escrow until close? And what about the contingency budget?

Second, the entire deal hinges on paying off bond debt for the Coliseum and Oracle Arena. AASEG (and its investors) want to close the deal sooner — but the city can’t legally transfer the title of the Coliseum site until it has paid off the outstanding bond debt on the stadium and the arena.

In order to speed up that process, AASEG agreed to pay for the city’s portion of the arena debt a year ahead of schedule, while the city will still repay the stadium debt.

If the city can’t pay back the stadium bonds, AASEG has the right to walk away from the deal entirely, including getting its $10M from “Payment One” back in full. Alternatively, if AASEG is unable to pay the arena bond early, the city may be entitled to keep the $10M.

Third, AASEG has the right to back out of the deal all the way up to the evening of November 6, 2024, coincidentally (or not) just one day after the election and one day before the first payment is due. AASEG would lose their $5M deposit, but wouldn’t be on the hook for anything else.

The timing is interesting. What, if any, political calculus is AASEG doing with the possibility of Thao being recalled and multiple of their city council champions (Kaplan, Bas, Kalb) potentially out of office?

Far from certain

Any changes to the original deal would need to be approved by city council members.

Ramachandran, Gallo, and Reid — who said they did not get a head’s up on the deal before it was announced by Thao — called for an emergency meeting on October 7.

Councilmembers Kaplan, Bas, and Fife failed to show up, so the meeting was canceled due to lack of quorum, but not before the former three members could convey their dismay and disbelief over this process and lack of transparency.

This deal is far from done. Regardless of whether the deal goes through or falls apart, Oakland is left in an extremely vulnerable position.

Without a deal, we will have wasted half a year on a botched deal, be left with a $63M budget emergency, and have a measly $5M souvenir to show for it. And if Thao gets recalled, she will have left Oaklanders with the worst parting gift imaginable.

If the deal does close next May, Oakland will still face the $100M gorilla of a deficit, with next year’s budget due just a month later in June 2025. Only this time, we won’t have another Coliseum to sell.

Update (October 10, 2024): Added screenshots comparing escrow language from original agreement and amended agreement.

“Is it a smart move to sell a revenue-generating capital asset to pay for operating expenses that the city can’t afford? This would be like selling your house to pay for your credit card bill!”

Clearly the answer is No. None of us would do that in our own finances (I hope). The obvious thing to do is the hard work of prioritizing services - instead of the 20% cut across the board approach. Prioritizing forces strategic thinking, and discipline to make the tough decisions, because there will be lots of those decisions needed to be made in order to balance this city’s budget. There also needs to be lots of focus placed on economic development, and what it will take to make people want to invest and do business in Oakland. That should be the goal, not selling an asset to bring in one-time money to spend on an ever growing abyss of a structural deficit…

Thanks for this. I work for City of Hayward and I compare our staffing levels to Oakland and am amazed at the difference. Population alone doesn’t explain it. It would be interesting to compare number of positions per capita. For example I read Oakland has over a hundred attorneys whereas in Hayward I think it’s around 6 for a population of 160,000. Similarly the number of engineers in the transportation department in Oakland was over a hundred I believe and Hayward has maybe 6? Also I hear they still work remotely in Oakland. That’s ridiculous, Hayward public works department is 3 days a week minimum in the office. The sale of the coliseum site for no bid should be illegal.